Researchers probe molten rock to crack Earth’s deepest secrets

New research focused on the quantum structure of elements under extreme conditions has implications for understanding Earth's evolution, interpreting unusual seismic signals, and even the study of exoplanets for insights into habitability.

Deep inside rocky planets like Earth, the behavior of iron can greatly affect the properties of molten rock materials: properties that influenced how Earth formed and evolved.

In fact, the evolution of our entire planet may be driven by the microscopic quantum state of these iron atoms. One special feature of iron is its “spin state,” which is a quantum property of the electrons in each iron atom that drives their magnetic behavior and reactivity in chemical reactions. Changes in the spin state can influence whether iron prefers to be in the molten rock or in solid form and how well the molten rock conducts electricity.

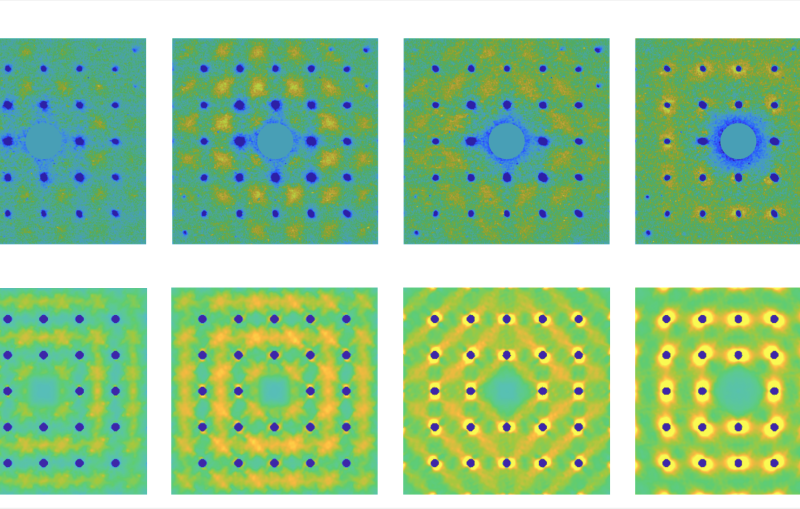

Until now, it’s been challenging to recreate the extreme conditions in these molten rock materials, called silicate melts, to measure the spin state of iron. Using powerful lasers and ultrafast X-rays, an international team of researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Universite ́ Grenoble Alpes, Laboratoire pour l’Utilisation des Lasers Intenses (LULI), and Arizona State University overcame this challenge. They showed that at extremely high pressures and temperatures, the iron in silicate melts mostly has a low-spin state, meaning its electrons stay closer to the center and pair up in their energy levels, making the iron less magnetic and more stable.

The results, published Friday in Science Advances, support the idea that certain types of molten rock might be stable deep inside Earth and other rocky planets, potentially lending a hand in the creation of magnetic fields. The research has potential implications for understanding Earth’s evolution, interpreting seismic signals, and even the study of exoplanets.

“In terms of exploring Earth’s history, we’re investigating processes that took place over 4 billion years ago,” said collaborator Dan Shim, a researcher at Arizona State. “The only way to study this is by using modern technology that operates in femtoseconds. The contrast between these immense time scales is both eloquent and startling: it’s akin to the idea of a time machine.”

Asteroid bombardment and magmatic oceans

About 4.3 to 4.5 billion years ago, early Earth underwent intense impacts, getting pummeled by asteroids as large as cities. These impacts produced so much heat that they could have completely melted the outer layers of the planet, creating a deep ocean of molten rock.

“It’s been theorized that under the immense pressure of these impacts, the molten rock may have became denser than the solid rock,” said collaborator and SLAC scientist Arianna Gleason. “This denser magma would have sunk towards the core, capturing the chemical signatures of that era. Some believe remnants of this magma layer may still exist today, holding clues from 4.5 billion years ago. Volcanoes like those in Hawaii could be releasing these ancient chemical signatures, providing us a glimpse into Earth’s distant past.”

At shallow depths, molten rock takes up more space than the same material when it’s solid. But as you go deeper and the pressure increases, this difference decreases. The inclusion of iron, especially its spin state, plays a big role in determining these properties. Prior research has shown mixed results about the spin state of iron in similar conditions: some studies found a rapid change in iron’s spin state under high pressures, while others saw a slower, more gradual change.

This new study provides the first direct look at iron’s behavior in real molten rock under extreme conditions.

“While we can glean a lot from studying rocks and fossils, some aspects of Earth’s early history are lost because few records from that time exist,” Shim said. “That’s what makes this study unique. Earth’s formation was a tumultuous process, involving intense impacts and resulting in a globally molten rock layer. The pressure in this layer was immense. We study this by simulating the conditions through laboratory experiments.”

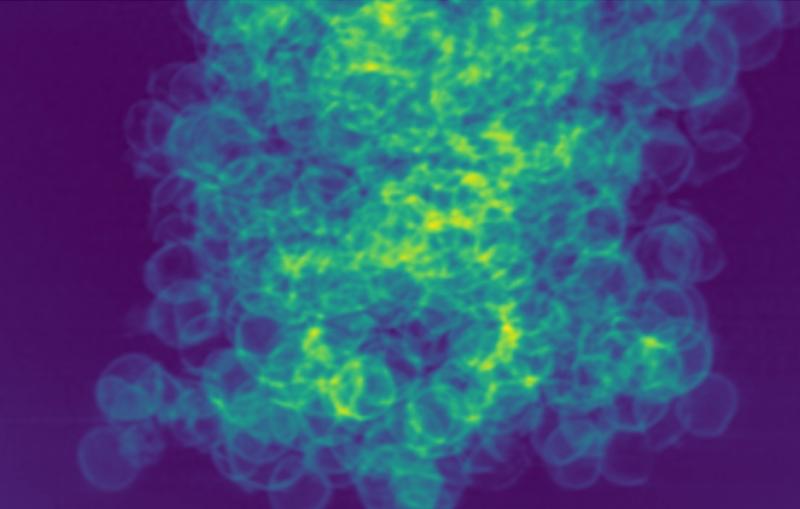

At the Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) experimental hutch at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), the team was able to recreate the extreme pressures that would have been found in early Earth’s magmatic ocean by blasting samples with powerful lasers that transform the solid material into a silicate melt in a matter of nanoseconds. Then, the scientists used femtosecond X-ray pulses from LCLS to study the electronic structure of elements like iron under these extreme conditions, providing insights into how electronic configurations change under different conditions and revealing that the molten magma did indeed become denser than a solid under specific conditions.

“By understanding Earth’s internal dynamics, we can refine models of tectonic movement and other geological phenomena,” Gleason said. “Moreover, as Earth’s layers are interconnected, these findings have implications for climate science.”

Understanding our planet

In this research the team concentrated on low iron content melts. But as material rains down towards the Earth’s center, it’s theorized to absorb more iron, making it denser. To follow up, the team plans to study melts with higher iron content. They also hope to experiment with melts containing some water, furthering our understanding of Earth’s water cycle and climate.

The research could also shed light on peculiar seismic velocities deep within Earth’s mantle. These anomalies have puzzled scientists for decades. Some theories suggest these zones could be remnants of magma from 4.5 billion years ago, while others believe they result from tectonic plates that have sunk into the Earth’s interior, spreading low melting point material. By comparing different hypotheses using seismic imaging, the team aims to determine the origins of these zones and distinguish between ancient and more recent materials.

“As technology advances, we’re at the forefront of addressing grand challenges that range from mineralogy to climate science, connecting various research areas,” said SLAC scientist and collaborator Roberto Alonso-Mori. “The sheer volume of information we can gather has transformed our capabilities. It’s a game-changer. It’s exhilarating to develop novel techniques and apply them to pressing questions with such a diverse team.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was supported in part by the DOE Office of Science and the National Science Foundation.

Read a related article from Arizona State University.

Citation: S.H. Shim et al., Science Advances, 20 October 2023, (DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi6153)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.